Guignard Kyoto Collection

Calligraphy triptych “long life/Jurōjin/happiness” 寿/寿老人/福 | Kanō Tsunenobu 狩野常信 | 1636-1713

Calligraphy triptych “long life/Jurōjin/happiness” 寿/寿老人/福 | Kanō Tsunenobu 狩野常信 | 1636-1713

Couldn't load pickup availability

Kanō Tsunenobu had “blue blood” from Japan’s most influential painting institution, the Kanō School, which decisively shaped Japanese art history for five hundred years in its many enormous studios. His father, Kanō Naonobu, was a highly respected painter, and his uncle, Kanō Tanyū, with his studio at the beginning of the 17th century, was the flagship of the institution and of Japanese painting in general.

Kanō Tsunenobu became an apprentice to his uncle at the age of 15, as his father had already died in 1650. This also secured Tsunenobu's career, which brought him the highest titles and honors. At the emperor's request, he even executed paintings in the imperial palace, in the Shishinden Hall.

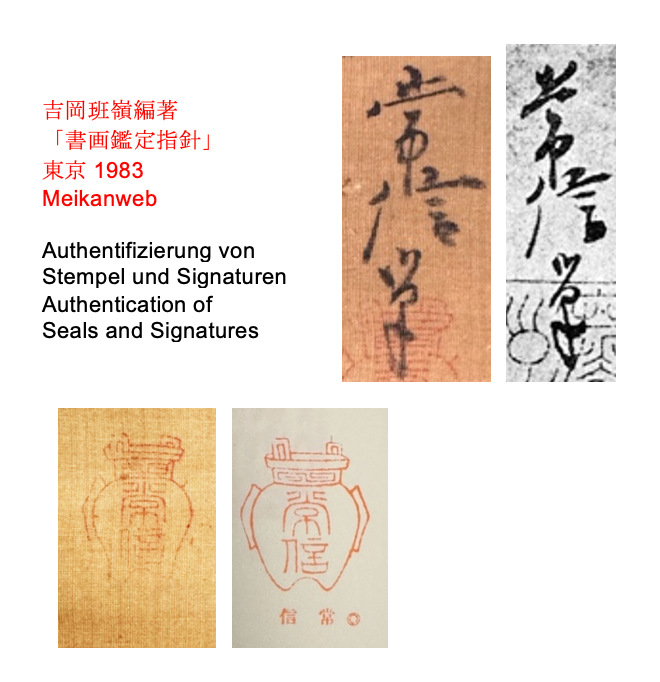

This New Year's triptych depicts Jurōjin, one of the Seven Lucky Gods of Japan, in its center. He is shown as an old, wise man, accompanied by the thousand-year-old crane, and leaning on the back of a sacred white stag. In this image, we encounter Tsunenobu as a master of form: the trio is elegantly and effortlessly inscribed within a harmonious circle. The two calligraphic panels framing the lucky god are traditional. Calligraphic variations of the two congratulatory characters "Good Luck" (福) and "Longevity" (寿) (here in their old form 壽). One hundred variations of each are presented, some of which have only a very difficult-to-detect formal relationship to the basic character. Since we have two images before us showing the collection of one hundred variations, we can see that they were developed in parallel. Collections of character variations were probably invented in late Han China, but had already reached a mature form by the Tang dynasty (618-907).