Guignard Kyoto Collection

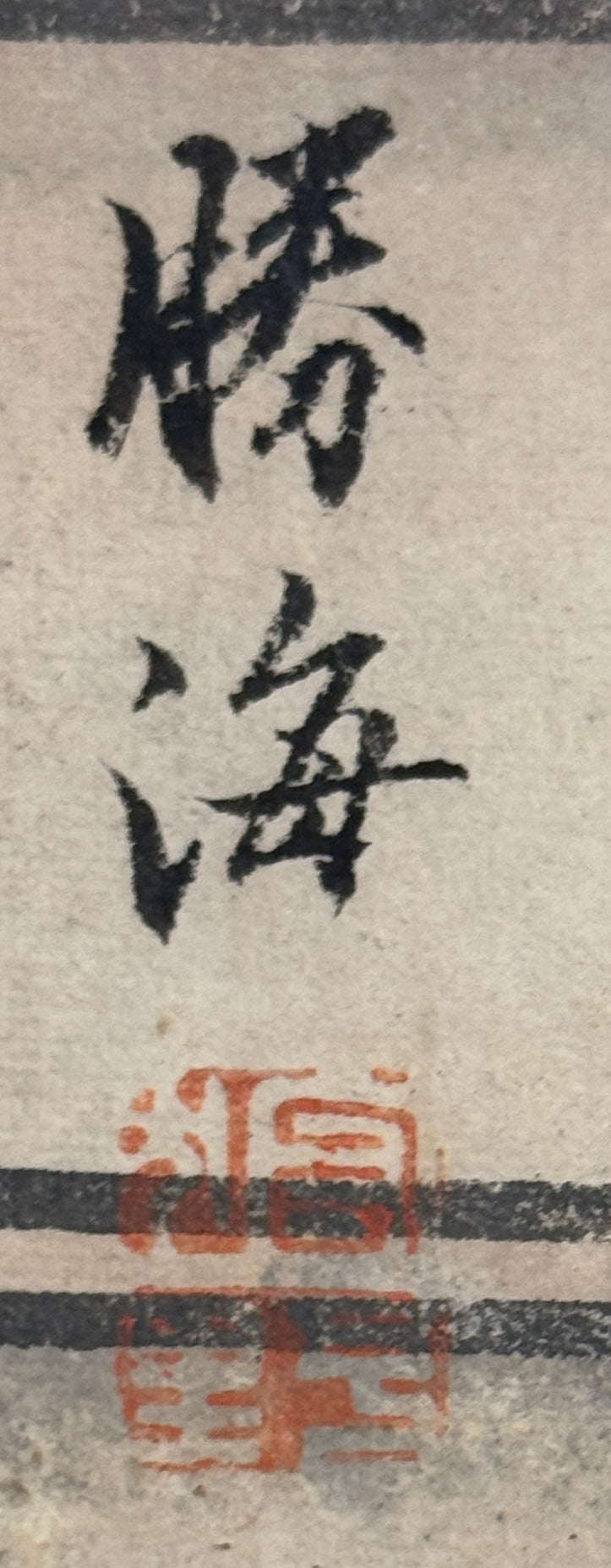

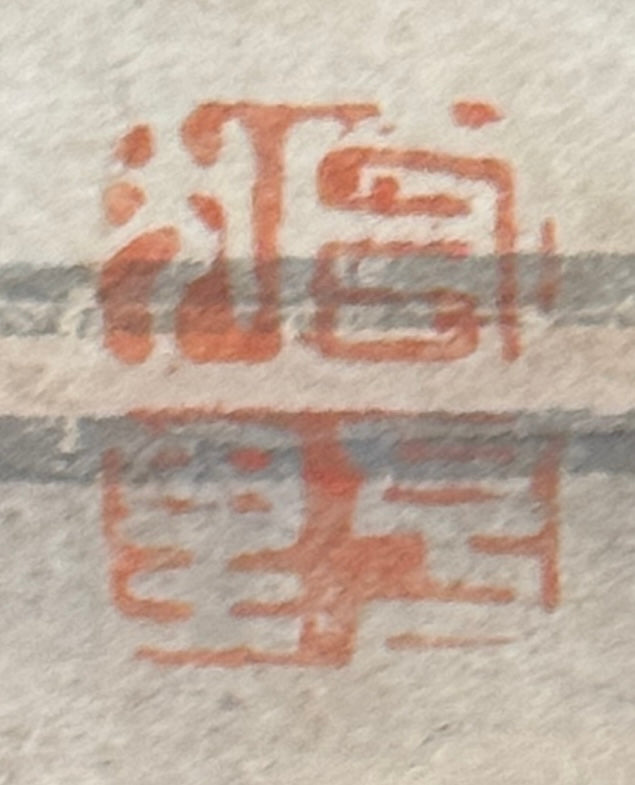

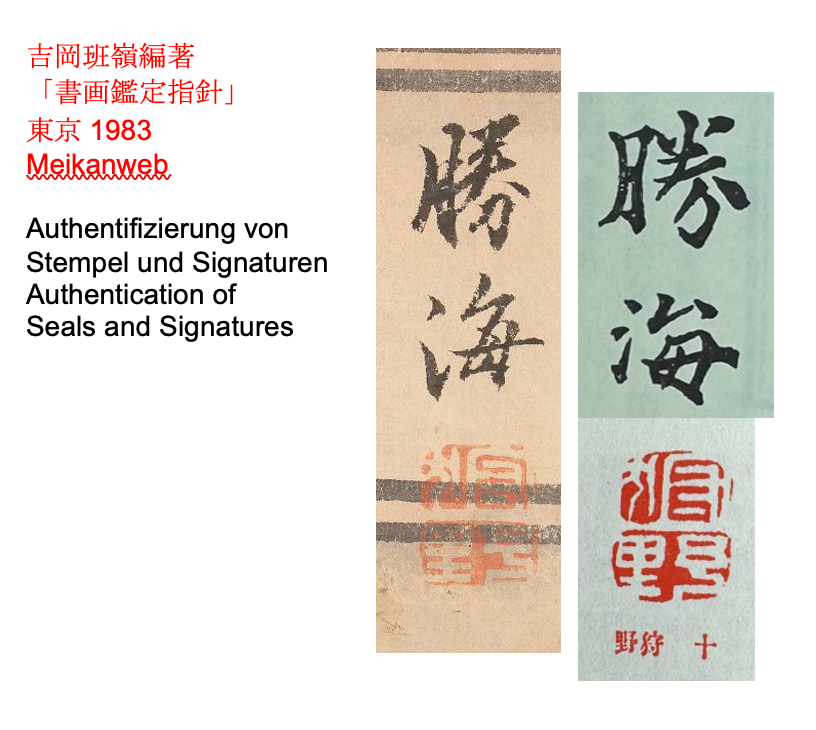

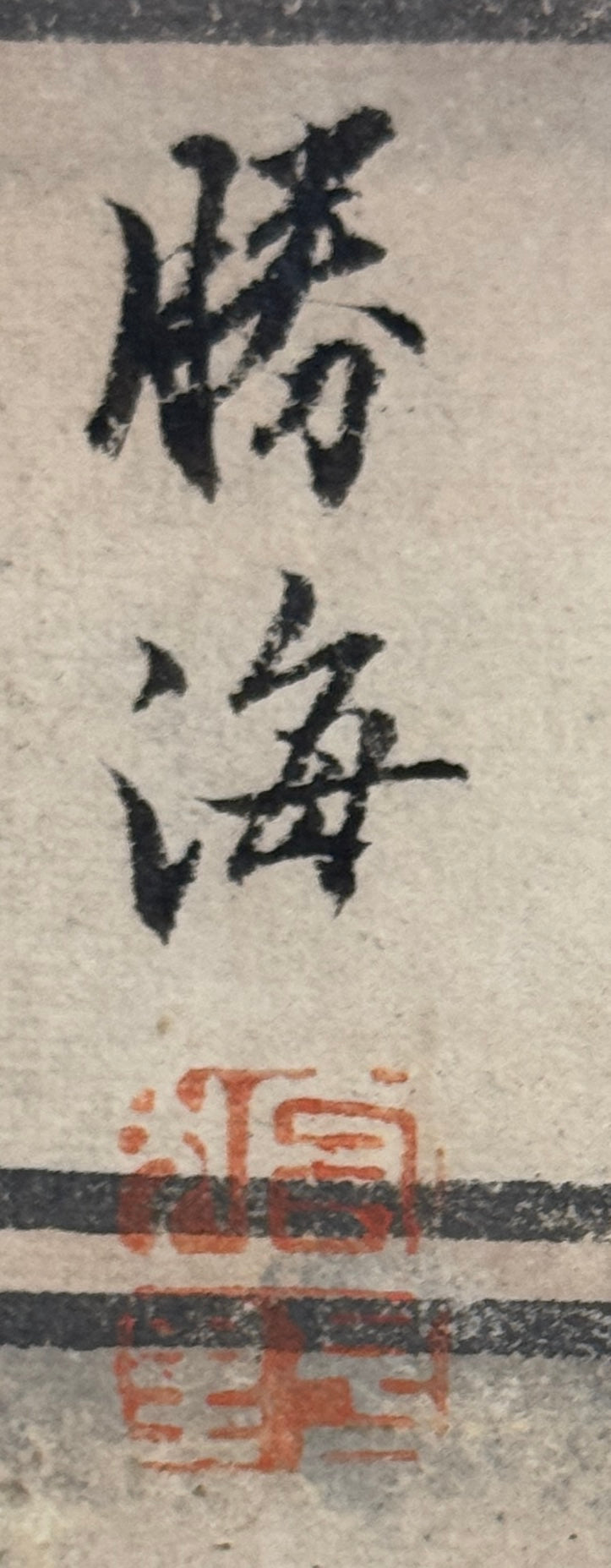

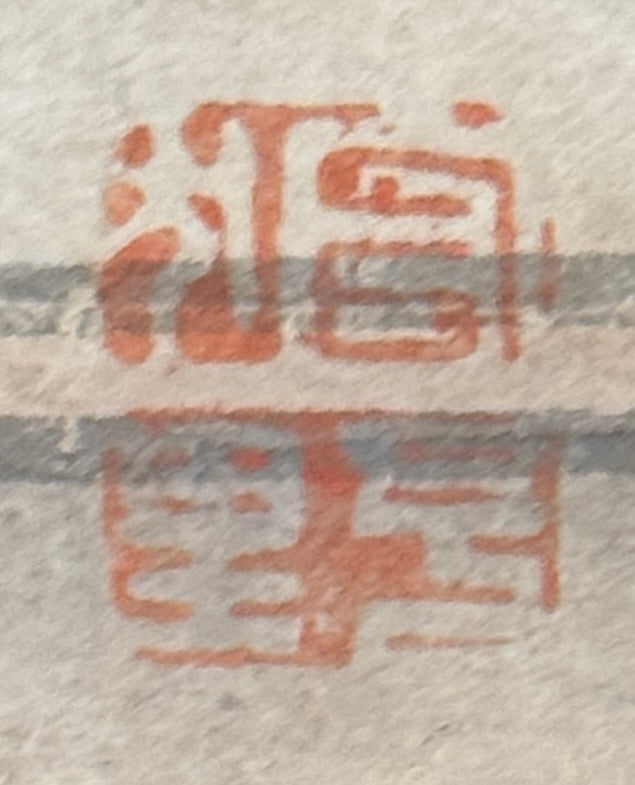

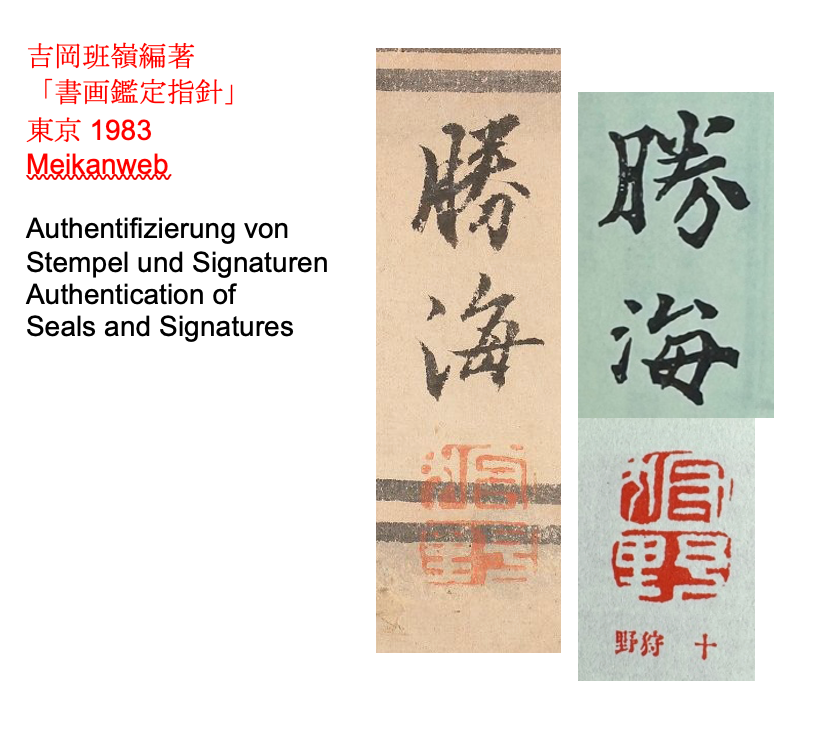

Diptych two horses | Kanō Hōgai 狩野芳崖 (signed Shōkai 勝海) | 1828-1888

Diptych two horses | Kanō Hōgai 狩野芳崖 (signed Shōkai 勝海) | 1828-1888

Couldn't load pickup availability

Kanō Hōgai is considered the last great master of the Kanō School, which had been the most influential and largest art institution in Japan since the 16th century. Countless masters of Japanese painting emerged from this school – whenever a young talent sought further training, they would immediately seek out a Kanō master. However, with the end of the Edo period (1603-1867) and the loss of feudal privileges, this school, with its strict motif guidelines, languished; it could no longer renew itself. Kanō Hōgai was an exception. He recognized the signs of the times and, after the Meiji Restoration (1868), worked with the most progressive minds of his time – with the painter Hashimoto Gahō and the pioneering thinkers Okakura Tenshin and Ernest Fenellosa. Only after this political and social upheaval did he call himself Hōgai; before 1868, his name was Shōkai, as he signed this painting. However, since he only used this name when he was 20 (before that, he signed with Shōrin 松隣), we can date this diptych to the end of the Edo period, to the period 1848-68.

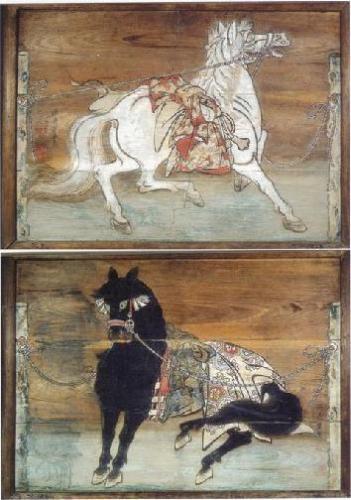

The theme is also traditional. Depictions of fiery horses are known primarily from ema . Ema 絵馬 were sometimes large wooden panels (some painted by famous artists such as Kanō Sansetsu (1589-1651)) that were offered to Shinto shrines. They replaced donations of horses, as it had long been believed that the god of the shrine would ride out at night and would mount a stately horse for this purpose. However, shrines did not need countless horses for their deity, and so painted horses were offered as substitutes.

What's great about this diptych is how the painter's compositional approach captures the horses' energy. (In the left panel, he seems directly influenced by Kanō Sansetsu.) Simply capturing the animals' wild behavior isn't enough; the exuberant energy must also be indirectly perceived (if the image is to be considered art). Hōgai works with the architecture: The horses behave boisterously in low stables—they appear cramped because the wooden frame of the stable obscures part of their bodies. Below and above the horses are various layers of wooden sheds and roofs; they are perfectly stable in their emphasized horizontality. The wooden floors are also decisively slanted, as if meant to prove that stables are perfectly safe from the powerful fury of an enraged horse. With such harsh geometric rigor, the horses' outburst of energy and power is emphasized in rich contrast.