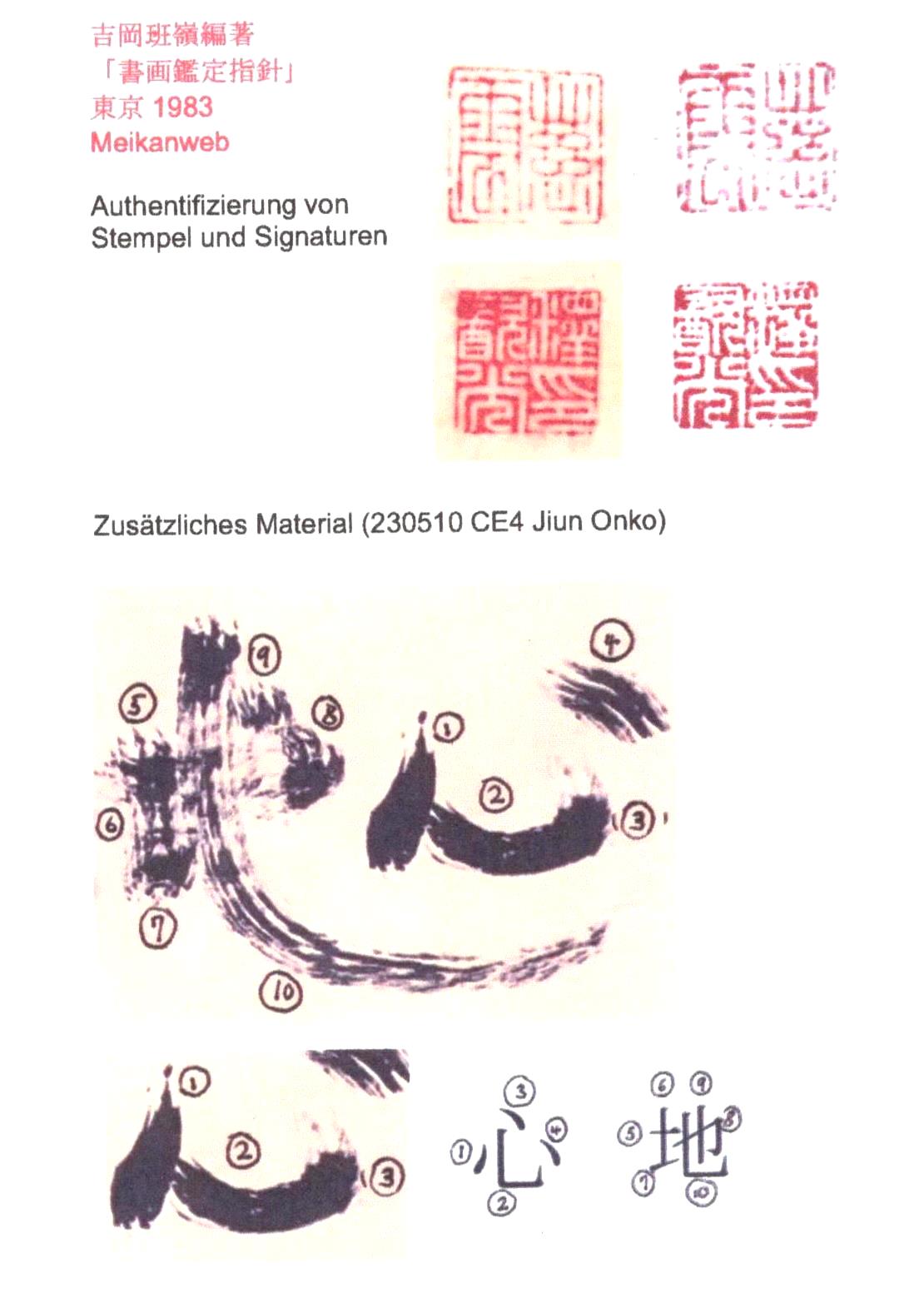

Guignard Kyoto Collection

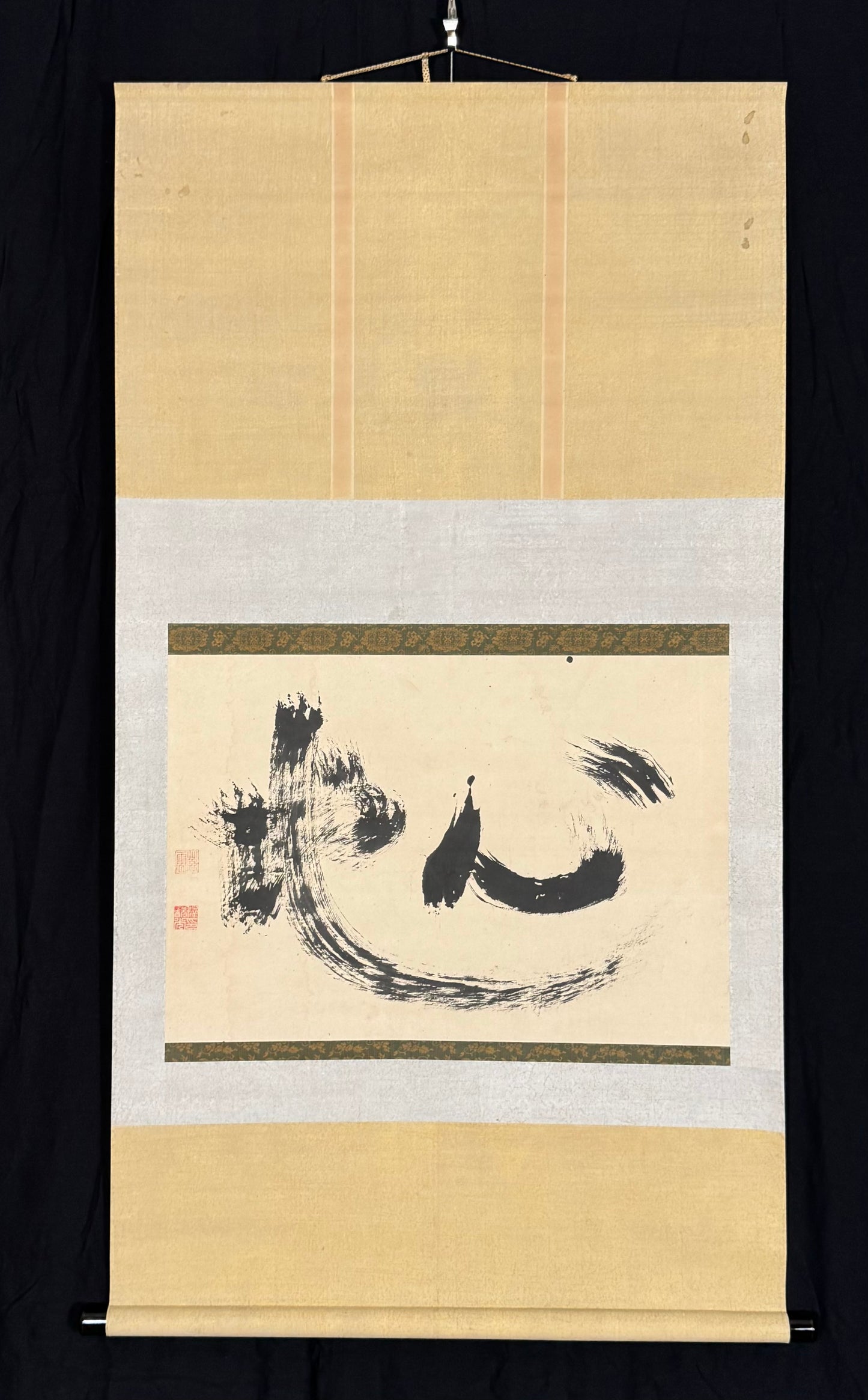

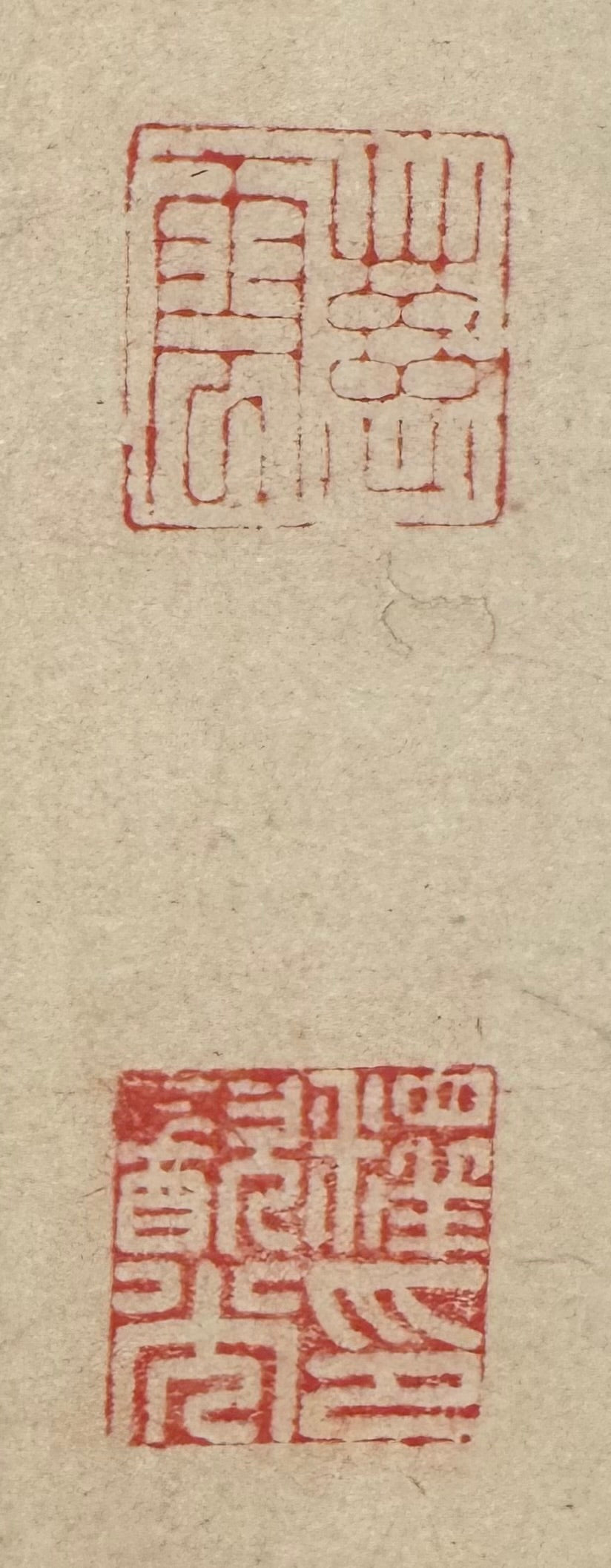

Calligraphy kokochi “(well-)being” 心地 | Jiun Onkō 慈雲飲光 | 1718-1804

Calligraphy kokochi “(well-)being” 心地 | Jiun Onkō 慈雲飲光 | 1718-1804

Couldn't load pickup availability

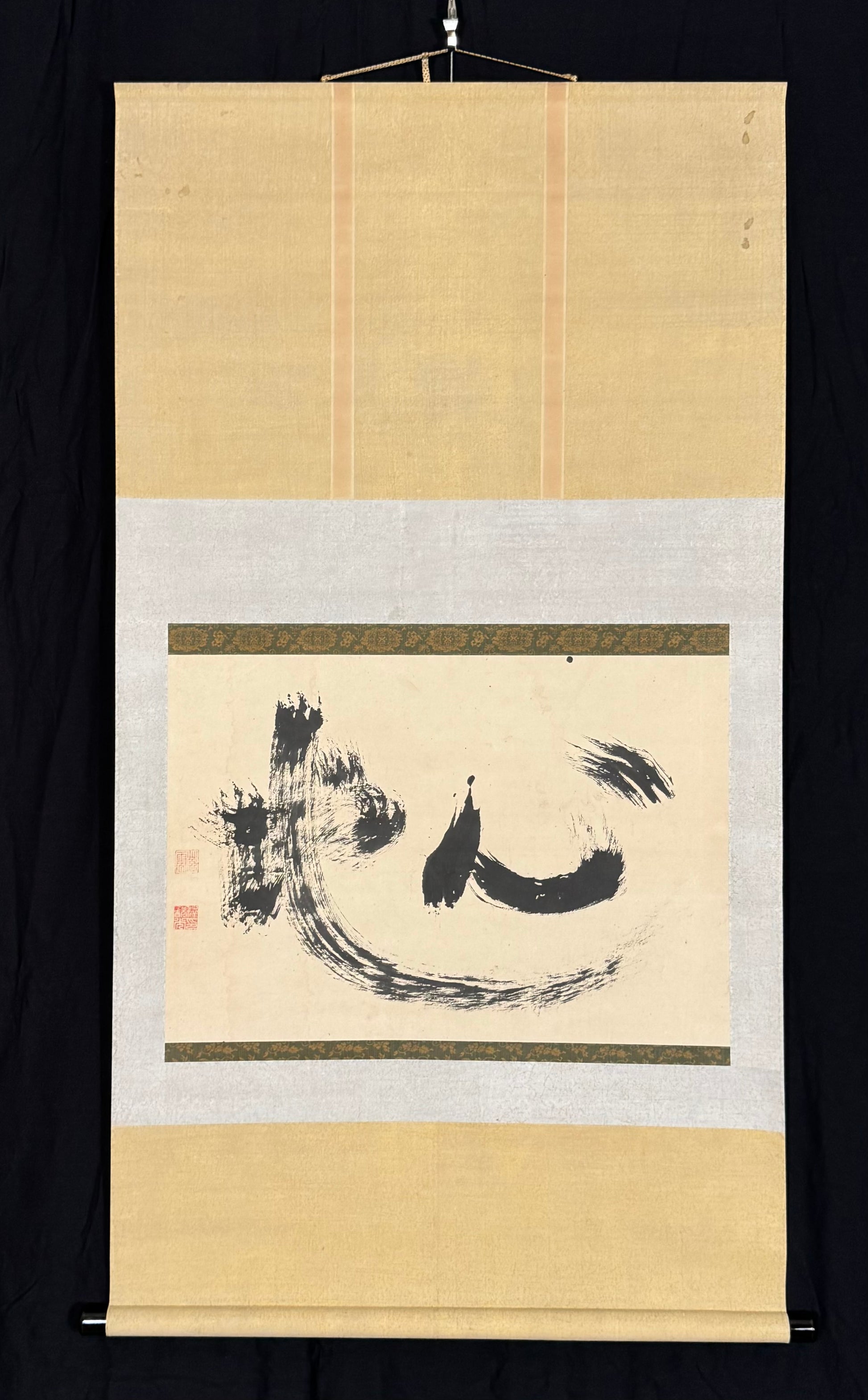

Jiun Onkō was actually a highly educated Shingon priest, but his interest lay less in esoteric Buddhism than in Zen. Many of his calligraphy works are exemplary examples of Zen. Typical for some of them is a thick, bristly brush, as was used in this calligraphy. On the one hand, Jiun rejects seductive suppleness and elegance, but on the other hand he is forced to combine small sequences of strokes. But this is in keeping with his Zen spirit, which does not bother with small details, but wants to get straight to the essence.

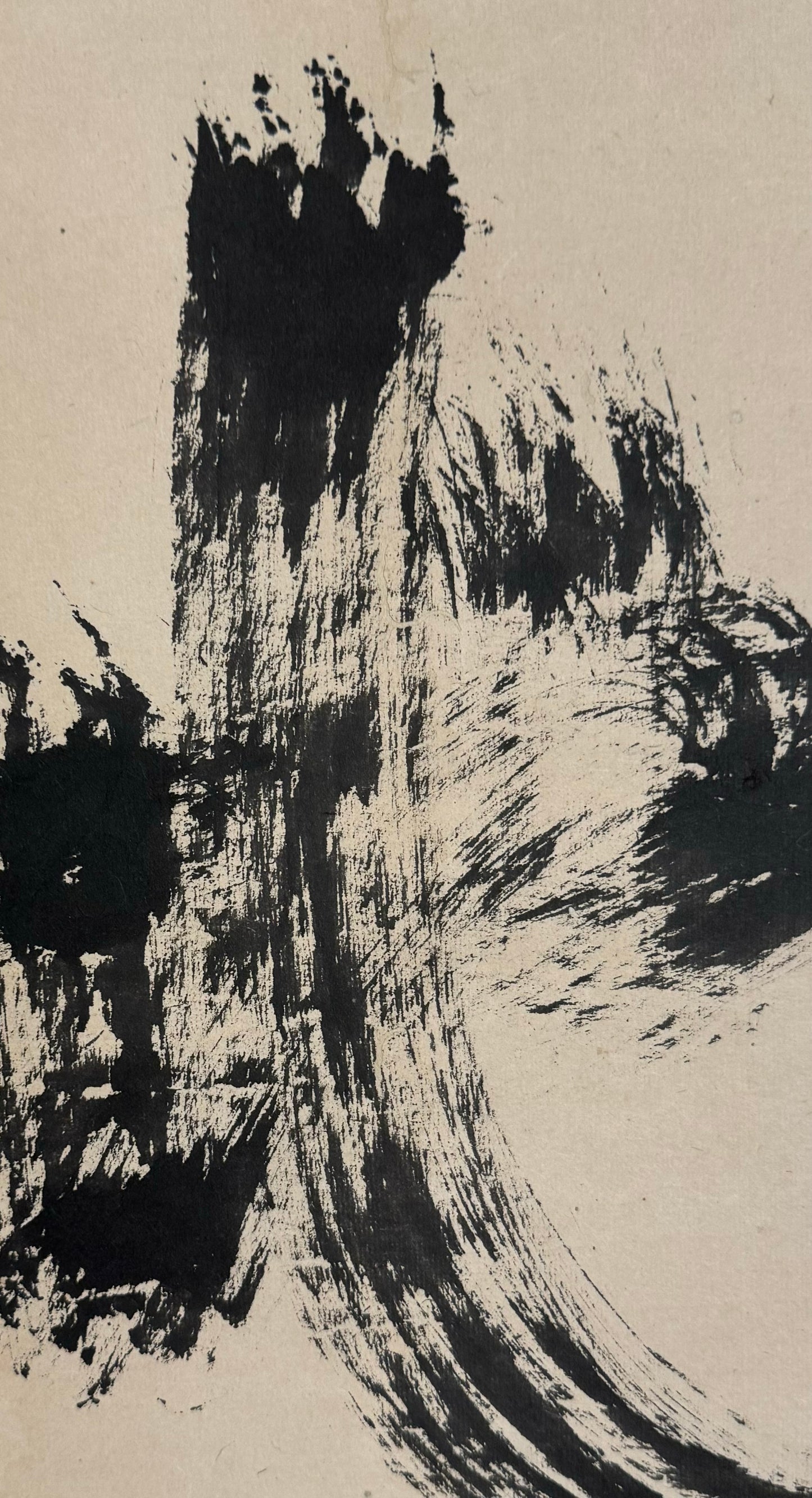

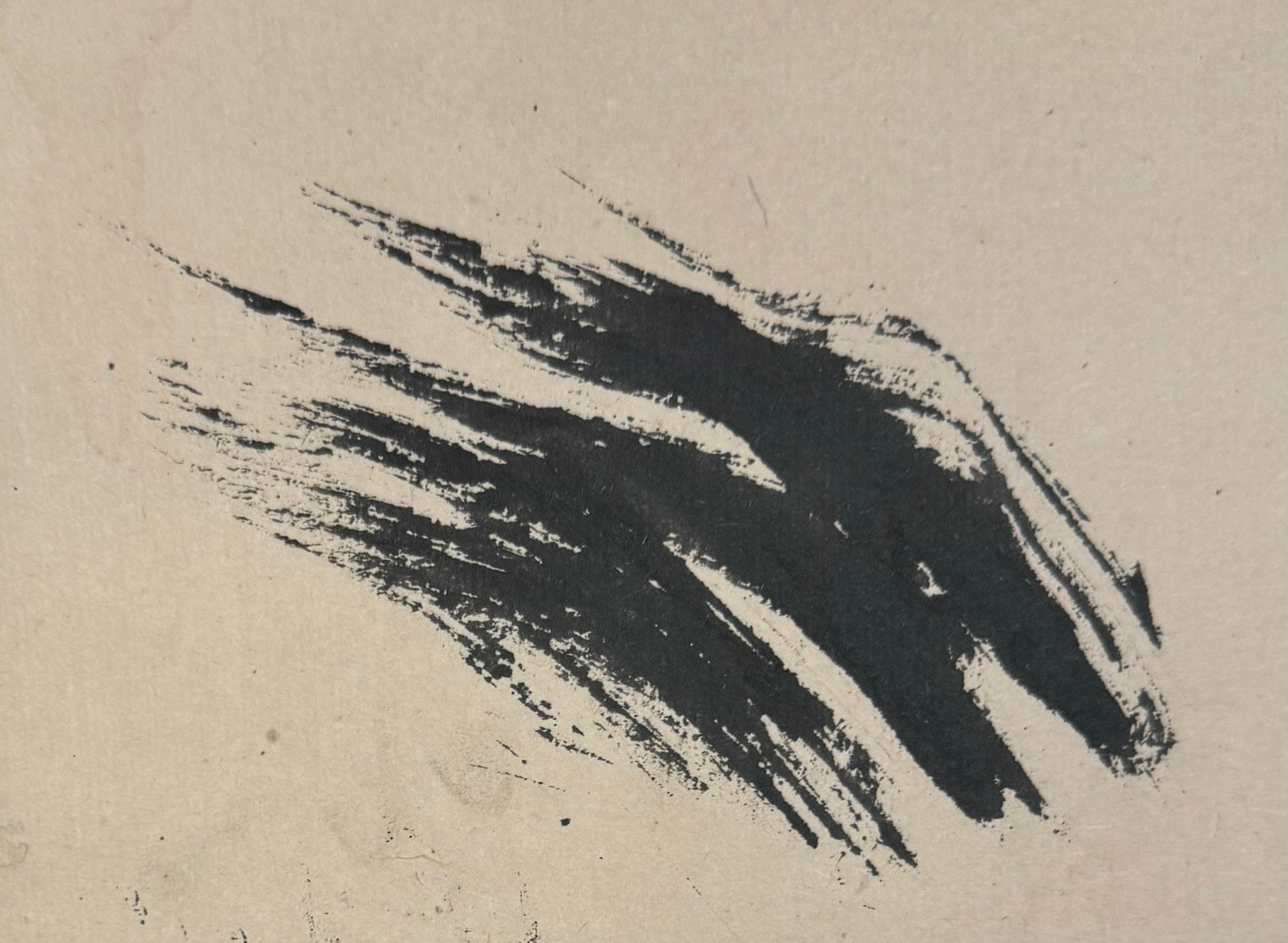

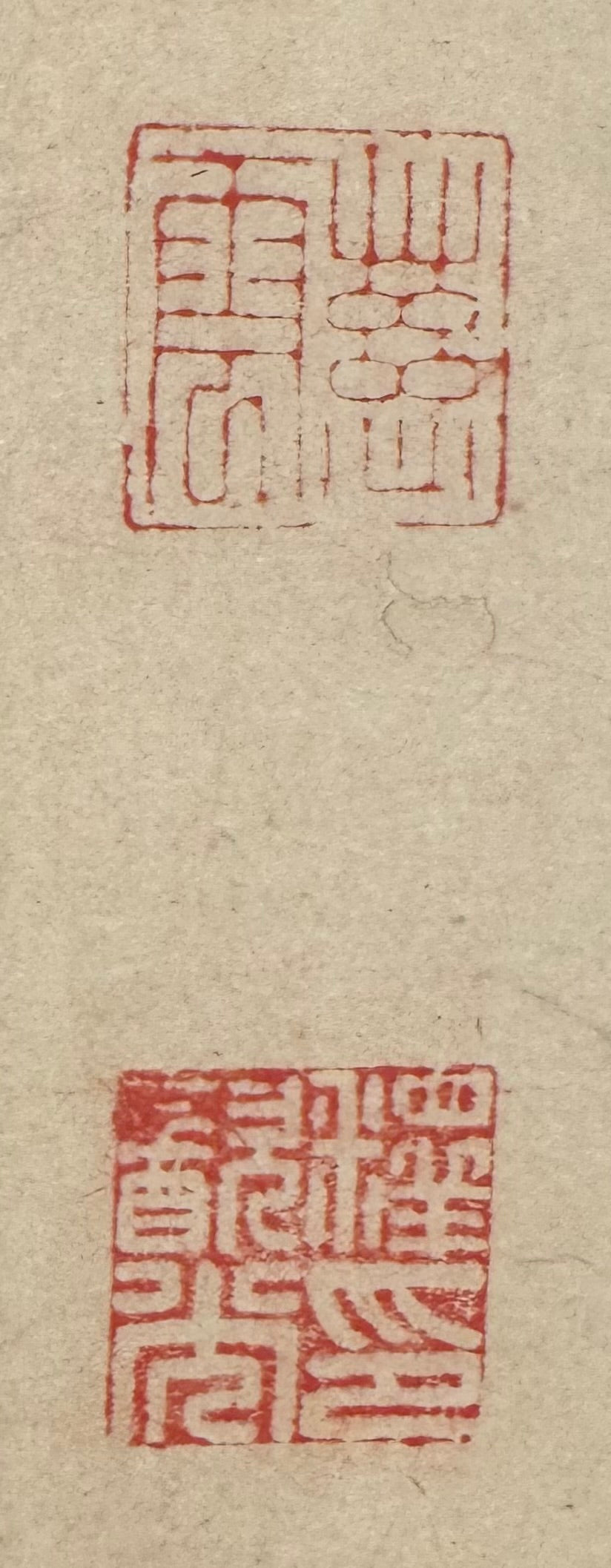

With the calligraphy of kokochi "(well-being)", Jiun is probably breaking new ground - this combination of characters is common in colloquial language, but hardly known in calligraphy. The normal use of the term in everyday language is: kokochi ga yoi心地が良い, which can be translated as "well-being", "comfort", etc. Kokochi alone just means "well-being" and is rarely used in isolation. Nevertheless, the combination kokochi is actually very telling in terms of content: the first character (on the calligraphy on the right) is "heart", and the second character (on the calligraphy on the left) is "earth". The combination of characters therefore describes the state when the heart is "grounded". In Asia, this is the basis for physical and mental (well-being)

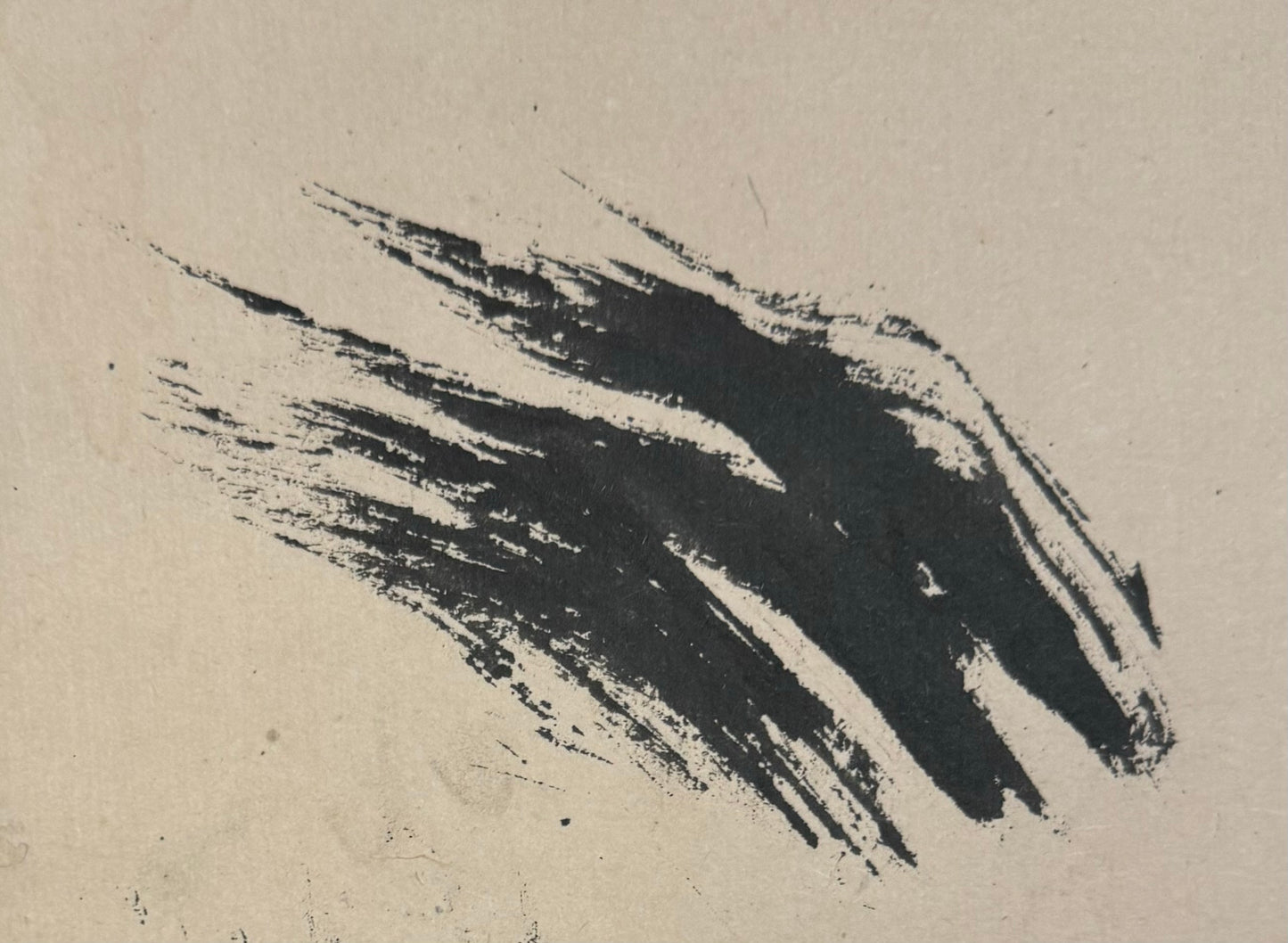

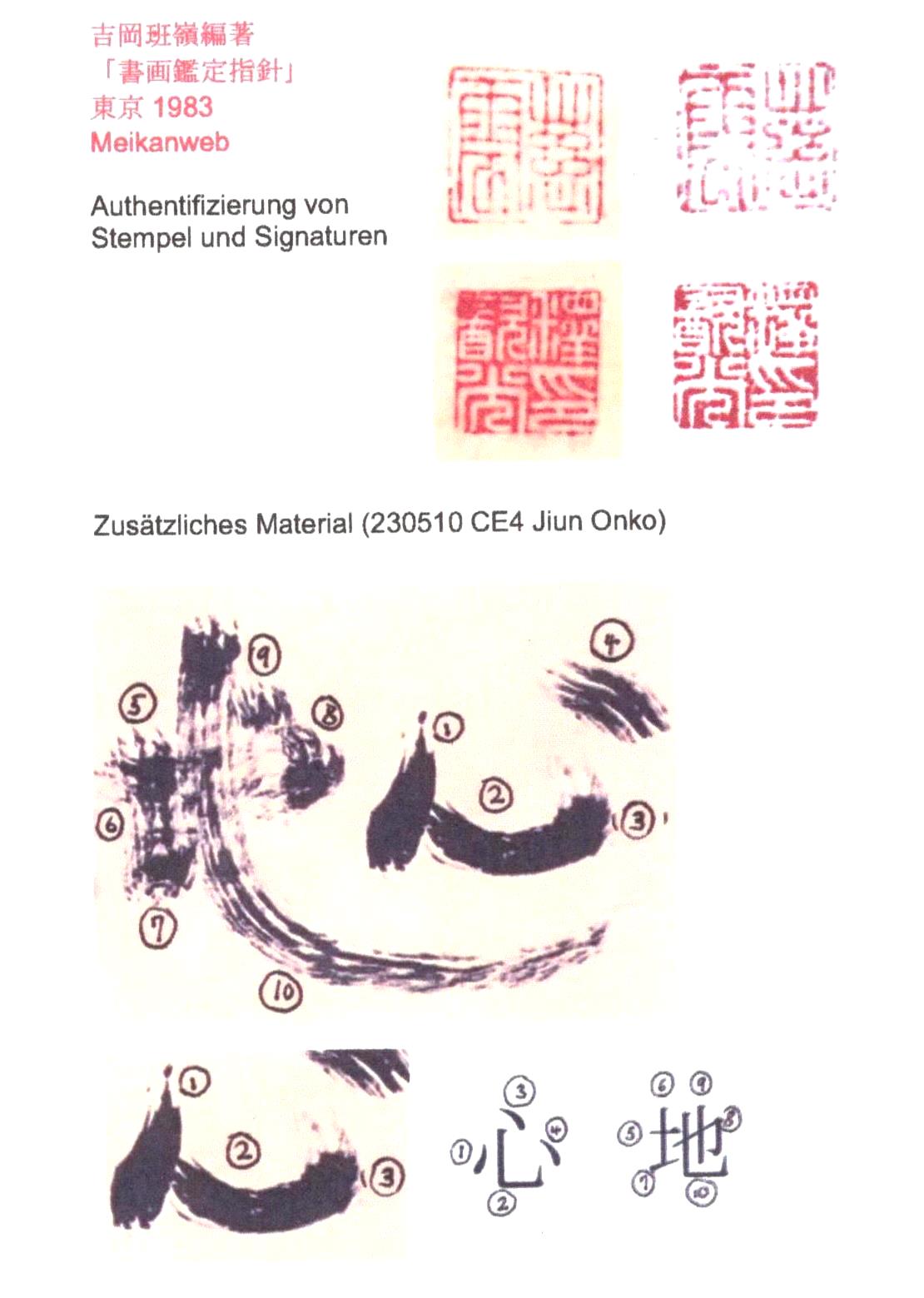

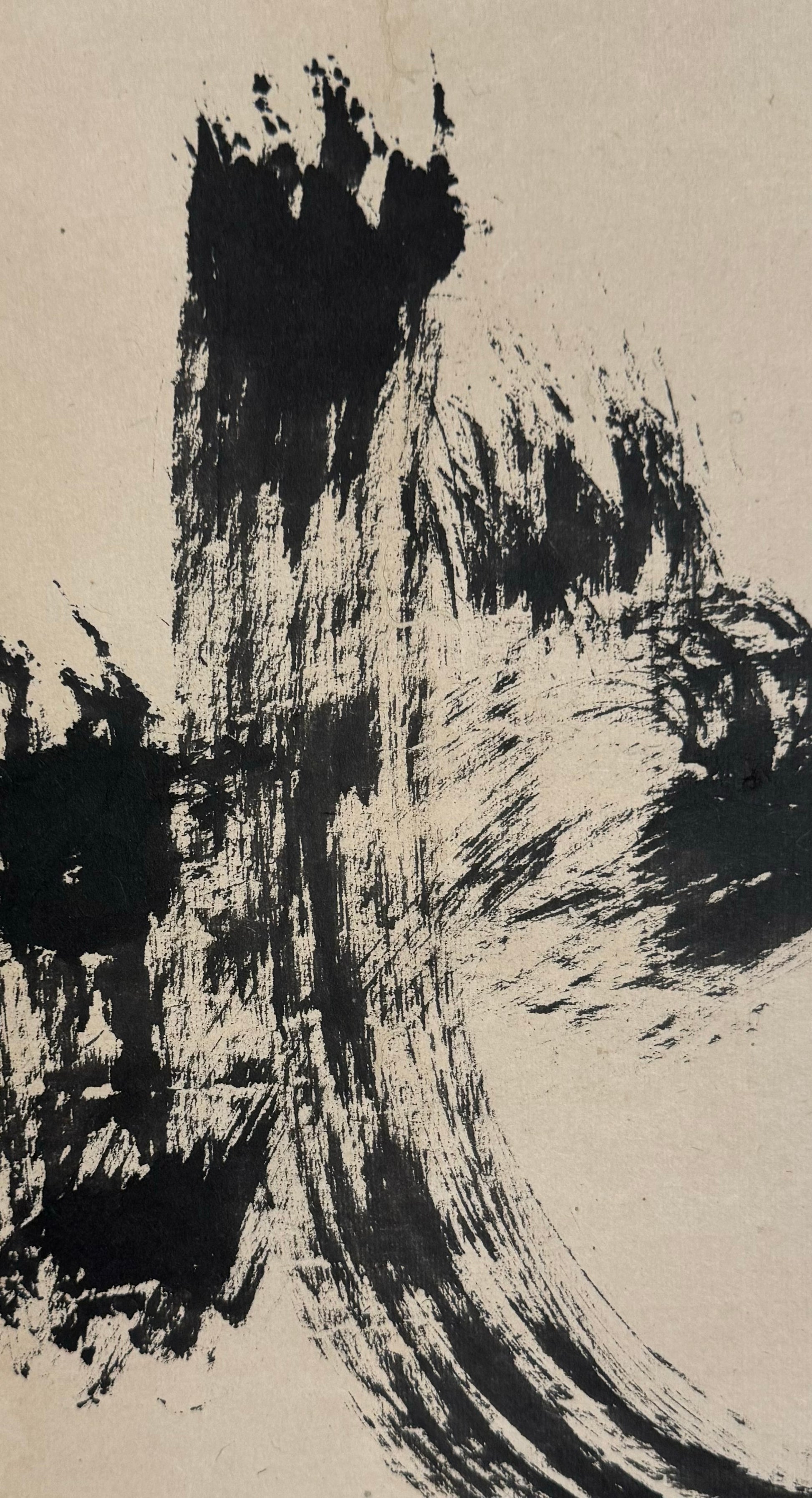

The character for "heart" kokoro心is often calligraphed as a single character. But here it seems - at least at first - as if this stroke sequence is already too complicated for Jiun; he designs stroke ③ only as the end of stroke ② . Normally, when calligraphing kokoro, stroke ④ is painted relatively heavily as the "end" of the writing process. But here the brushstroke has almost only a passing character and is as bristly in style as the entire left character for "earth" chi地.

With this “Earth” sign, Jiun allows himself remarkable simplifications: At the beginning, the five individual strokes ⑤ - ⑨ are reduced almost exclusively to dots, because for Jiun the absolutely most important stroke is the final stroke ⑩ , with which he sums up the combination of characters with great pleasure. What is more, the “heart” lies almost like in a cradle on ⑩ , and at first glance one thinks that the last line of “heart”, the number ④ , a continuation of No. ⑩ , which is certainly not the case.

But this gives Jiun's change to heart calligraphy a special ambiguity: the integration of line ③ into line ② mentioned above was painted with a brush that was still heavily saturated with ink, so that lines ① - ③ are immediately similar to the character for human being hito人. This nuance creates a feeling of a soft embeddedness not only of the heart, but of the whole person. This is the basic feeling that is important to the Zen priest: the whole person should become one with the earth, he must feel spiritually ("heart") protected by it. Only then can he himself become a part of the world as a whole.