Guignard Kyoto Collection

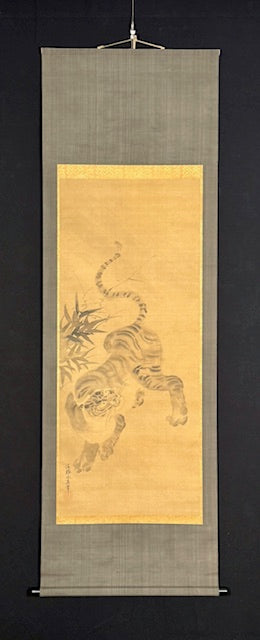

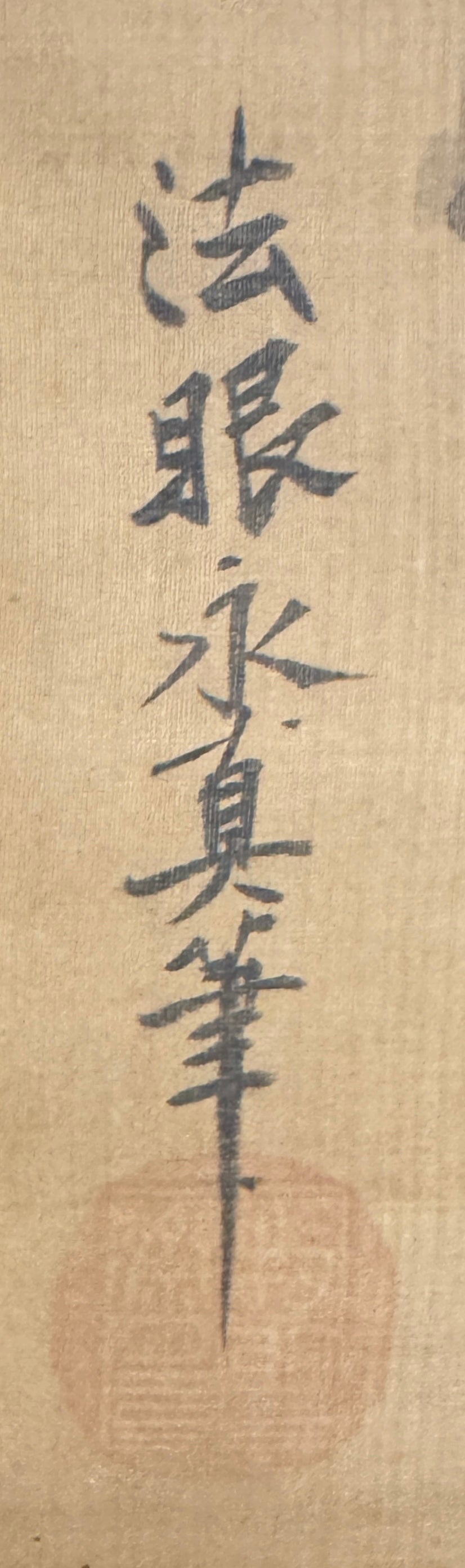

Tigers | Kanō Yasunobu 狩野安信 | 1614-1685

Tigers | Kanō Yasunobu 狩野安信 | 1614-1685

Couldn't load pickup availability

Kanō Yasunobu held a special position within the all-powerful art institution of the Kanō School. His father, Takanobu, died when he was still a child, and so Yasunobu, as a painting adept, came into the care of his eldest brother, Tanyū, the outstanding figure of the Kanō School in the 17th century. His other older brother, Naonobu, was also considered one of the great masters. With these two geniuses in the family, the younger brother's career as a painter was not easy. He also specialized as an art connoisseur and became an expert in authentication.

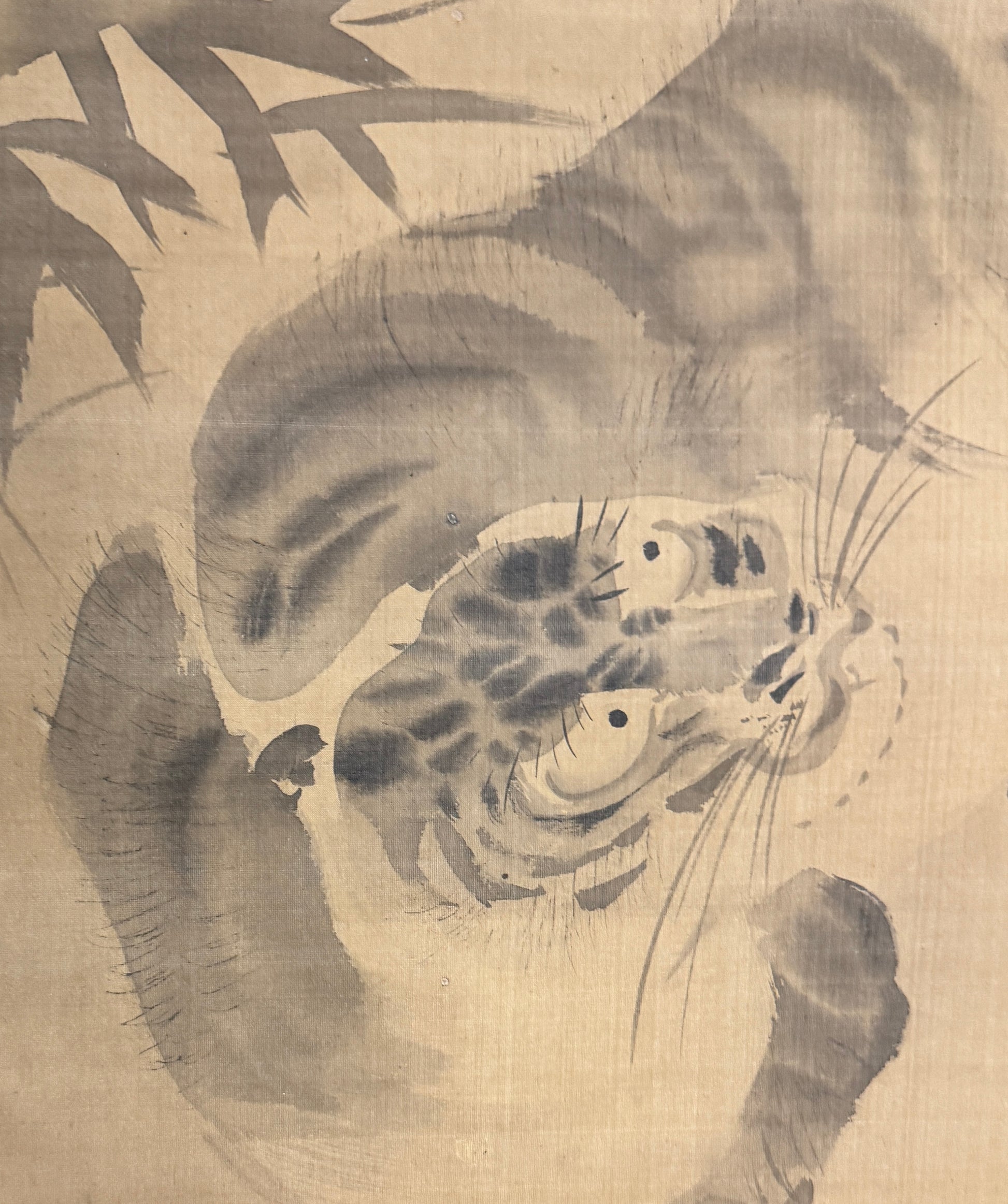

Not all of his legacy's works reach the level of the artistry of his two older brothers (art experts agree on this), but time and again, paintings are found that are equal to the skill of Tanyū and Naonobu. Doesn't this also apply to this tiger painting? Painters of the early 17th century knew tigers only from painted models – it wasn't until the 19th century that Japanese were able to see a live tiger for the first time in Edo (Tokyo). There is therefore always something unreal about such early tigers, meaning that tigers were more symbols than zoological realities. This painting could therefore also be part of a diptych, the right-hand panel of which depicts a dragon; the pair would then have the theme: “Ruler of the Earth” versus “Ruler of the Skies”.

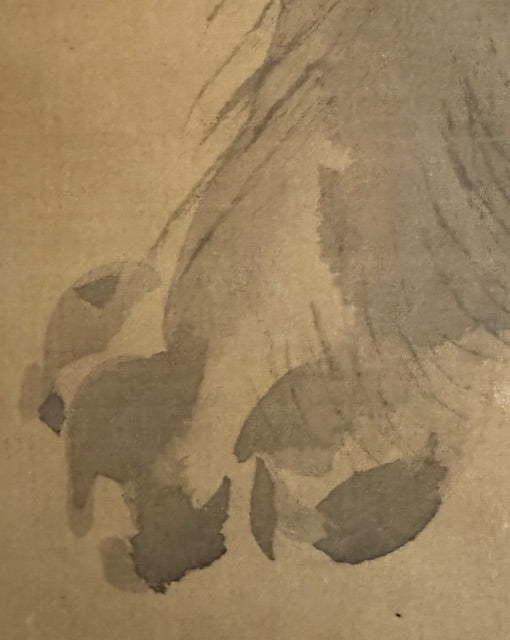

What makes this tiger painting admirable is, first of all, the use of ink, which—with the exception of a few bamboo leaves and a few strips of fur—is quite watery. Looking at the paws, for example, it's striking that the agility of the brush and the speed of the strokes harmoniously match the lightness of the light ink. In addition, the feline agility of the "ruler of the earth" is permeated by an S-shape. This is not only clearly evident in the tail's curve, but can also be felt in the design of the hindquarters in relation to the left hind leg, as well as in the relationship between the torso and the angled head. A strict (and sensible) formal principle thus seems to permeate this body in a way we rarely find in tiger depictions of this period.